saturdays are for the 1 in 5 single men who have no close friends

read to find out more about loneliness! heartbreak! feminist theory! a complete and utter abasement of the scientific method!

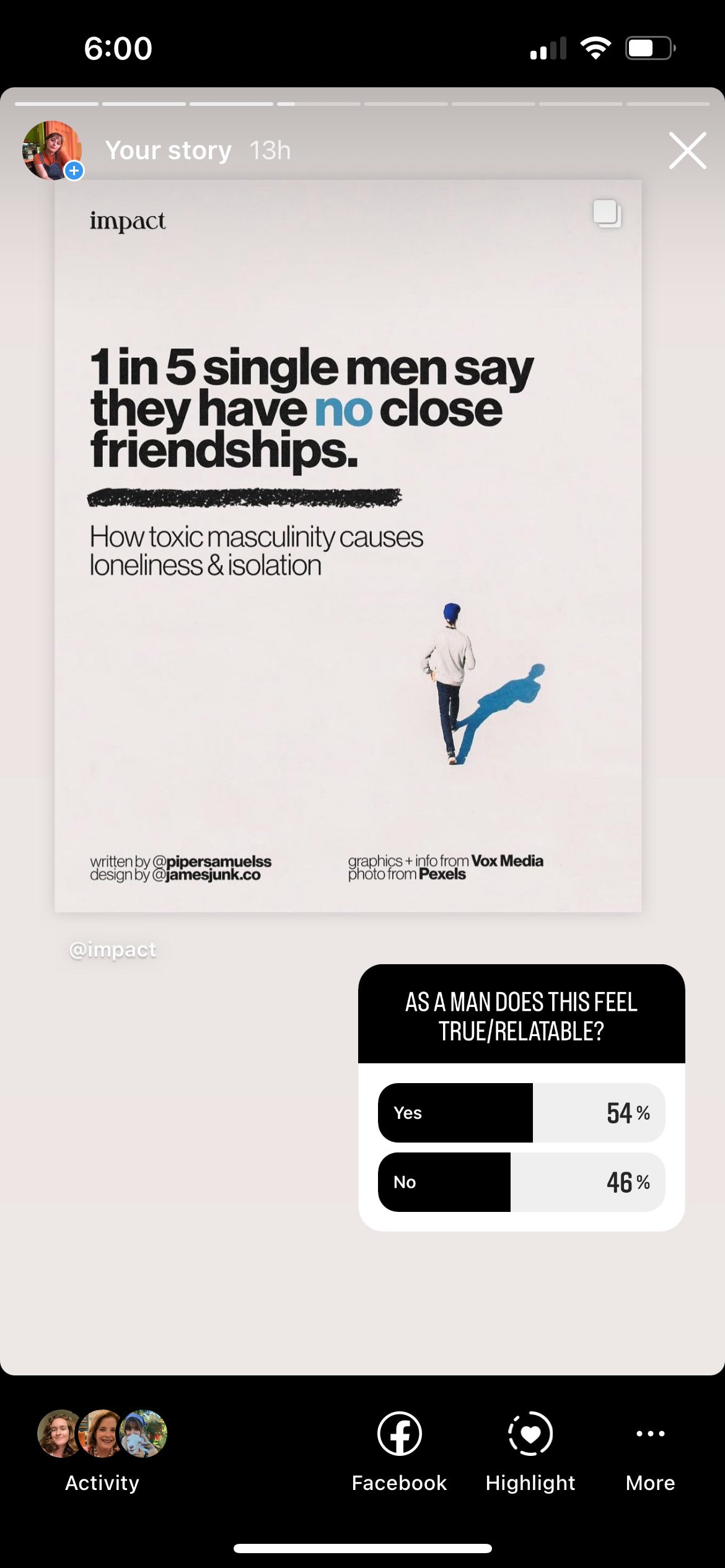

They’re everywhere— they’re someone’s son, brother, cousin, father. But they’re definitely not your friend. Lonely men are among us. According to an infographic posted on my instagram story (primary source vibes), 1 in 5 single men say that they have no close friendships. Vox and the New York post have both cited the same study by the Survey Center for American Life. But you don’t have to take their word for it. As a loyal reader of my newsletter, you can get all your information directly from the men in my dm’s whose opinions I solicited for the sole purpose of satiating my own curiosity and bringing the girlies crawling to this newsletter, hungry for answers. (That’s my way of saying thank you for being here, by the way.)

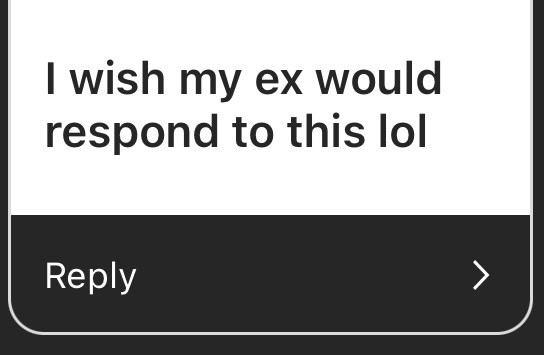

But it’s true, I asked the self-identified men who follow me to please slide into my dm’s (for a limited time only!) to tell me what they think of this statistic. Does this feel true to you? If yes, why? I asked. Do you resonate with this the same way I might resonate with a statistic that said 1 in 2 women have found a therapist for their boyfriend (actual study pending, and more on this later).

I’ve compiled a synopsis of some of the most compelling responses for your reading pleasure. But first, this is of course a highly unscientific case study so here I go with the caveats: I am followed by mostly white, cis, presumably straight, to some degree economically, socially, educationally and/or demographically privileged men. And the ones who responded of course can’t speak for all men— we know how they feel about the term “all men” don’t we? But a few responses gave me new insight into a question that I’ve turned over in my head and in conversations with my friends countless times. And I know that the study says “single men”. And I am admittedly writing under the assumption that if partnered straight men were to eliminate the option of “girlfriend” or “wife” as one of their “close friends”, I think that the numbers would be even higher (or I guess lower— if you know how math works please unfollow me this is not a safe space for you). If the follow up question to this study was “how many of your close friendships are with a woman and/or a woman you are romantically involved with?” how would that have changed the results? To be fair, when I asked the insta boys how many of their close relationships were “mostly with other men” or “mostly with other women” or “equal”, the results came back about 50/50 mostly men to mostly women. But since this is all unscientific and mostly anecdotal anyway, I think I can also take into account the many women who responded to my story eager to have their roles as the sole emotional caretakers of their male friends and boyfriends explained by my findings. Listen, as much as I love providing pro-bono mental health services while simultaneously being seen as a sexual object (she’s double threat!) I think it’s time we interrogate what exactly is causing this dynamic in the first place.

Anyways, here are some of the takeaways:

Many men wrote to me describing a set of primitive, ardent social rules that restrict them from building emotional intimacy with one another. They referenced homophobic remarks, accusations of “softness” and “weakness” as not only declaratively negative qualities but decidedly untoward in the context of an all male social space. To put it plainly, being vulnerable with your boys, it just isn’t done.

One respondent said, “vulnerability is almost unanimously preyed upon, even among close friends..[as a way of] leveraging of a superficial status”. He said that his friends would make fun of each other for being “emotional”, and the respondent himself admitted to policing displays of emotional vulnerability among his friends, even when he knew better. He laid out a clear cause and effect: men would be punished for opening up with power checks disguised as humorous jabs. Their reliance on humor to enforce this structure is also interesting to me. It’s reminiscent of what women experience as the “feminist killjoy” effect. It’s the stick in the mud feminist who can’t take a joke. And the reason we can’t or won’t is because what women know as members of an oppressed social class is that jokes are not just jokes, they are strategically delivered warnings. Jokes tell a deeper story than just an attempt to make someone laugh, they are carrier pigeons of a crucial message: I do not condone your behavior right now, and I think you should stop. Men have been dishing these kinds of social-status-enforcing jokes for a long time, but it seems that in their friendships with other men they find themselves on the receiving end of it and are baffled to find themselves trapped inside something that resembles the killjoy’s conundrum.

Another respondent said something that I hadn’t heard before about this idea of loneliness and how it informs connection— or lack of connection— between men and other people. He described himself as having “lived this statistic” and when I asked why this is what he said, “it stems from this weird idea that people get in the way of me and my pursuit of happiness or the masculine urge for ‘life success’. So I have to cut them out and then that leads to me being isolated.” The respondent tied this way of thinking to enlightenment philosophy and of course, Big Daddy Capitalism. Big Daddy Capitalism prizes individualism and a maladaptive tendency to cut people out for fear that their humanness might pose a threat to the accumulation of capital. If there was a viral “that boy” aesthetic it would be a taut, protestant man taking on wall street armed with nothing more than an avoidant attachment style and a protein shake. He would move swiftly and decisively, unencumbered by loving, intimate and reciprocal relationships. The tragic irony of this cycle was not lost on the man who wrote this response, and in fact all the men who responded showed an interest in disassembling their coveted isolation. Yet they all seemed unsure about how to do it, and I was unable to decipher if the things they were all so readily expressing to me were things they had actually talked to their male friends about.

An experience that I can only assume other non-men can relate to is opening up to a man only to have him say something utterly unfeeling in response. I think of the 30 Rock scene where hypermacho Capitalist King Jack Donaghy attempts to comfort a distraught Liz Lemon with a broom.

Why are they so uncomfortable with our feelings!? One respondent offered an answer. He mentioned that growing up, he was instructed, either explicitly or by example, that he should “be strong for others” and not show his own emotions for fear that they might impede his ability to take care of other people. This then, he says, led to a general lack of empathy that he had to confront later in life when his close relationships demanded more from him, and he found it difficult to give. This one maybe feels obvious, but personally I had never made the direct connection between not showing your own feelings and therefore having little to no tolerance for that of others. It explained what was going on in those moments of frustrations when you’re crying or hurting and a man has no fucking clue what to do or how to help you.

If you find yourself at this point thinking, okay so men are lonely—but so what? (And I mean so what in the literary sense, the high school English teacher who asks you to rewrite your thesis statement until you posit an answer to the question.) What does it mean for our society, our culture, our systems that men are lonely and lack close friendships in disturbingly high numbers? Well, one response demonstrated to me how deeply this lack of connection can hurt us— regardless of gender, I think this scenario paints a bleak and informative portrait. One woman responded to my story to share about how the loss of a parent illuminated the differences between her friendships with other women and her brothers’ friendships with other men. She wrote that when her mom died there was a “noticeable difference” between the way her friends supported her and the ways her brothers’ friends supported them. She wrote, “Their friends struggle with showing support through vulnerability; they don’t ask my brothers how they are doing, they def are anxious avoidant, they don’t go ‘above and beyond.’” She said that her brother could “only vocalize his pain when drunk”.

I could write a whole other essay about the implications of what this person shared. There is so much there. But to keep it as succinct as possible for our purposes today: those are some serious stakes.

Pretty much all the men who responded spoke on internalized homophobia, the fear of appearing “soft”, “gay” or “needy” if they asked for a physical affection need to be met or if they shared feelings or expressed tenderness. They spoke of their need for closeness in such a way that revealed their belief that this need was some kind of moral transgression, even using carceral terms to describe it as “being exposed” as (insert gaysoftneedy synonym here), or being “accused of being” gaysoft or needy. And I find myself thinking not for the first or even for the hundredth time, the lengths that men will go to to not “be like a woman” is mind-blowing. And what does this chronic distancing from all things “feminine” reveal if not a subconscious or even explicit knowledge of the suffering and unfairness that women and all non-men face in this life. I put “feminine” in quotes here because it’s an indisputable fact that emotions are not intrinsically female qualities, however they are at this point so deeply correlated with femininity that when we see a man trying to fight the existence of his own feelings, what we are actually watching is a man try to fight any real or perceived shred of femininity inside of himself.

And finally, there are the feminist implications of it all.

The project of feminism is interested in this problem because the goal is always to get more free. I think right now, women and femmes and anyone existing without cis male privilege are the ones filling in the void of loneliness that many men feel. And that comes at a steep cost to us and our freedom. We are cosplaying as therapists and mothers and sex dolls and emotional cumrags all at once and sometimes even our profound love and affection for the men in our lives cannot salvage the damage that this undue burden causes us. I have been that lonely man’s sole keeper of all things emotionally intimate, secretive, shameful, difficult, anxiety-inducing. And the result of being that solitary lighthouse for a man is that his loneliness is transmitted onto me, as I now hold so much that I cannot put it down without also putting down someone’s entire emotional life. And so now I alone must bear it for him. We cannot be free or expressive or focused on other important projects when we are emotionally, spiritually, and mentally exhausted by the problems of our men. And I think the answer to “why” men are entrusting us with their emotional lives rather than other men comes down to the fact that simply, we are not men. We’d like to think that they open up to us because we are special and kind and caring and ask lots of good questions and are nurturing. And I think all of these things are true— we do have all of those great qualities. But what’s more important about us is that we do not abide by the social contract that exists between men. And even if we did know about the social rules that apply in settings between men and even if we did feel moved to enforce them, we as women lack the authority to do so.

If they’re anything like me, the moment that they read the statistic I posted on my story, there were a lot of women who had finished answering a question that men might not have been aware was being asked. If they aren’t turning towards other men for closeness, who are they turning towards? Well, boys, you might be looking at her.

This is such a brilliantly comprehensive, insightful exploration of the complex cancer that is patriarchy. I loved everything and especially this: "And I find myself thinking not for the first or even for the hundredth time, the lengths that men will go to to not “be like a woman” is mind-blowing. And what does this chronic distancing from all things “feminine” reveal if not a subconscious or even explicit knowledge of the suffering and unfairness that women and all non-men face in this life... When we see a man trying to fight the existence of his own feelings, what we are actually watching is a man try to fight any real or perceived shred of femininity inside of himself." Wow, wow, wow. You nailed it. Thank you for doing this research and writing it all up so powerfully. Oh and loved the "30 Rock" reference, too. Long live the comedic wisdom of Tina Fey!